Pueblo Style Architecture

Pueblo Style Architecture:

The development of the Pueblo Style as a local domestic building form can be directly attributed to James Bright, co-developer of Miami Springs. His business interest prior to South Florida had been in the Southwestern states and Mexico. The deployment team of Glenn Curtiss and James Bright in planning Miami Springs intentionally used architectural motifs generated from domestic architecture of the Pueblo and Spanish Colonel vernacular.

Miami Springs was to be an exclusive planned development using the variation of the popular national style to meet the competition of the area. Although Pueblo style was picturesque, it was far from at home in South Florida, although it did have a remote Spanish association. It was a promotional stage front as opposed to architecture that was well suited to Dade County’s climate. Its popularity quickly faded after the real estate collapse of 1926.

The Pueblo Style was a novelty style popular in the 1920’s. Its features recall the old Southwest reminiscent of a time when hand formed and crafted elements dominated domestic life. Its simple, modest forms are cousin to Mission Style.

Modern building techniques were used to transform the soft, hand molded forms into economically feasible structures. Clay block and wood frame construction replaced mud brick and hand formed stucco.

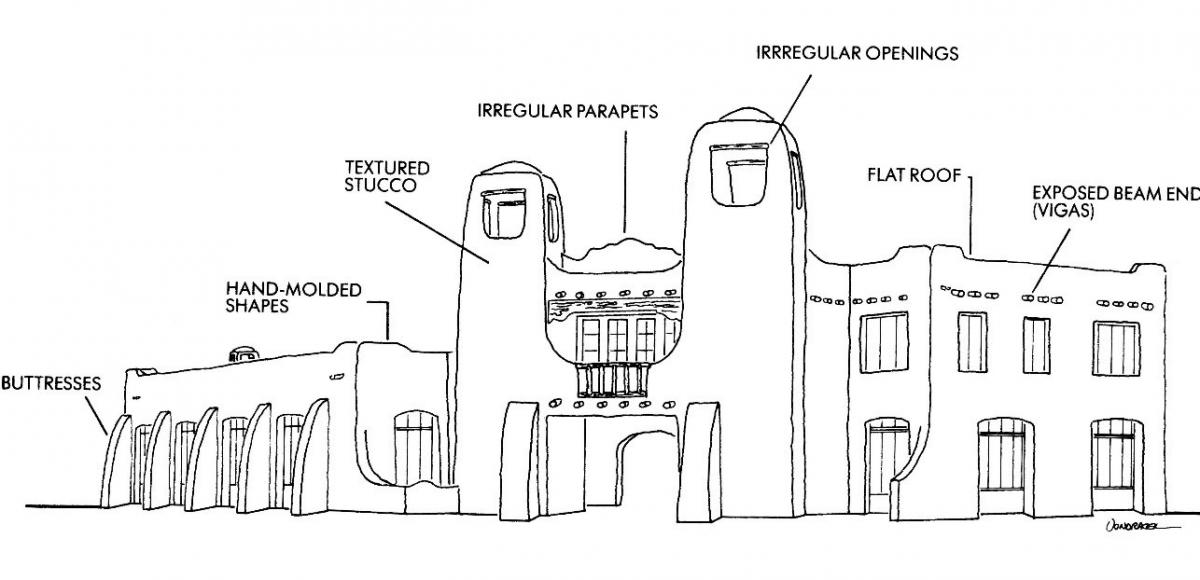

Key Distinguishing Features:

Faux earthy materials: Pueblo-Mission Revival construction imitates the appearance of traditional adobe Pueblo and Spanish Mission architecture, but uses concrete, stucco or mortar to simulate the effect of thick, rough and textured walls which are painted in earth tones.

Massive wood components: Heavy (often arched) doors, ceiling beams, porch posts and projecting decorative “rafters” are a striking counterpart to the stucco-covered exteriors. These rafters are called vigas and are usually exposed at the ends and extend past the roofline. Vigas are only decorative and serve no structural purpose. Vigas may be supported underneath by simple, squarish corbels (beam supports).

Enclosed courtyards: As traditional Pueblos and Missions were organized around a common space, Revival buildings often incorporate a courtyard, arcade or patio that may be either open, covered or fully enclosed. They are usually supported by Spanish-style wood posts made from the same wood as the vigas, and may utilize built-in benches, called bancos, which protrude from walls. Additionally, either inside or outside, there may be small carved niches in the walls designed for showcasing decorations, plants or religious icons.

Rounded exteriors with deep-set windows: Like traditional Indian Pueblos and Spanish Missions, Revival buildings feature small windows set deeply into the walls. Rounded corners on the doors and windows reflect the corners of the exterior walls as in the “parent” styles.

Flat or sloping roofs with parapets: Parapets are distinctively curved or shaped asymmetrical low walls that extend up above the roofline along the edges, in varying heights. Drainage canals for rainwater called canales sometimes extend through them. On less traditional Pueblo-Mission Revival buildings, low-pitched roofs are covered with rounded terra cotta-colored barrel tiles and – in ornate cases – a tower or bell cote (small niche for church bells) symbolizing a mission.

Stepped massing: Like traditional Pueblos, Revival buildings are based on rectangular forms. Although the Pueblo people often built massive communal living spaces reaching up to five or six stories, most Pueblo-Mission Revival buildings are limited to one or two stories. Multi-story buildings use this same stepped massing style, with stepped levels becoming progressively narrower toward the top.